Alpine Tunnel – An Engineering Marvel

Courtesy of Legends of America

Situated about 18 miles southwest of Buena Vista, Colorado is the historic narrow gauge Alpine Tunnel.

Once the highest railroad tunnel in the world, at an altitude of 11,523 feet, it was the first tunnel to be built through the Continental Divide. The Denver, South Park and Pacific Railroad began the work of connecting St. Elmo to Pitkin, Colorado in November, 1879 with a construction crew working at either end to connect the line. Anticipating that the mineral rich area would be the next big mining “bonanza,” as many as 10,000 different men worked to build the line and the tunnel at various times. A crew of around 400 worked steadily, but turnover was quick, as the men suffered through the cold, brutal work. Laborers, working for $3.50 per day, and explosives men, who worked for $5.00 per day, were often forced to go from their worksite to their cabins in groups in order to avoid being lost in the snow.

Denver Leadville and Gunnison Railroad engine number

199 emerges from stone Alpine Tunnel. Photo taken late 1800’s.

Excavation of the tunnel began in January, 1880 with plans to complete it within six months. But, those were ambitious plans, especially starting the project in the middle of winter. It would actually take the railroad more than two years to complete the tunnel and cost them far more than they had planned, coming in at about $300,000 and some $180,000 more than they had initially budgeted. Due to crumbling granite in the tunnel, over 400,000 board feet of California redwood was required to support and encase 80% of it.

The two crews met each other in the tunnel in July, 1881, but it would be another year before it was ready for the train.

When the first narrow gauge train came through in July, 1882, the tunnel was 1, 772 feet long, over two miles above sea level, 500 feet below Altman Pass (later renamed Alpine Pass) and the most expensive railroad tunnel built up until that time.

Beyond the west portal exit of the tunnel, stood the alpine Tunnel Station, the highest railroad station in the nation; as well as a turntable, water tank, stone boarding house, and engine house that was large enough to house six engines.

The rebuilt Alpine Tunnel Station today, Kathy Weiser, September, 2006.

Western Union Telegraph & Cable Office and two story boarding house, taken at the time when they were owned by Colorado & Southern Railroad, 1900, courtesy Denver Public Library.

Beyond the tunnel, the Denver, South Park and Pacific tracks continued on to Gunnison.

Once it was complete, the engineering marvel was a welcome relief to all of those who were previously required to haul supplies and mail back and forth over the treacherous passes of Tin Cup, Taylor and Altman.

All along the tracks were a number of small settlements, some to service the railroad and others that housed the many miners of the area. These included Woodstock, Quartz, and Sherrod, as well as Pitkin at the western end, and St. Elmo on the eastern end of the line.

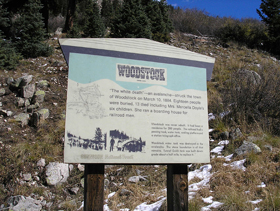

Even though the weather was harsh at that elevation, especially during the long winter months, things went relatively well for the line and the tunnel for the first several years. However, in March, 1884, the town of Woodstock was completely destroyed by an avalanche, burying 18 people, 13 of whom died. Six were children. The settlement, which had as many as 200 residents was never rebuilt. Most of its residents moved to nearby Sherrod and a new water tank for the railroad was built about ½ mile down the grade. All that remains today of Woodstock are a few stone foundations, some rotting timbers and a historic marker.

Due to the high elevation and the harsh winter conditions, the tunnel began to close during winters between 1887 and 1889 and again between 1890 and 1894. In the meantime, the Denver, South Park & Pacific Railroad went into receivership in August, 1889 and re-emerged as the Denver, Leadville & Gunnison line under control of the Union Pacific Railroad. However, that line, too, would go into receivership five years later.

In 1895, the tunnel faced two more disasters when, during the reopening of the tunnel after the winter, four crew members suffocated. Not long after, a train wreck occurred, killing two men near the tunnel in May.

The line continued to struggle financially until Colorado and Southern (C&S) Railway Company was formed with the merger of the DL&G, Union Pacific, and Denver & Gulf railroads in 1899.

The line was plagued with accidents and storms during its 30 year life. In 1901, a train with one passenger coach and ten loaded freight cars was completely buried by snow and in 1904, another train wreck occurred west of the tunnel. Two years later, a fire destroyed the engine house and another collision occurred inside the tunnel.

The historic Alpine Gulch Water Tank, on the trail prior to reaching Woodstock, has been restored, Kathy Weiser, September, 2006.

Finally, the railroad company gave up on the dangerous and accident prone tunnel. The last train came through in November, 1910. A decade later, the vast majority of all of the old track had been removed.

Today, the area is known as the Alpine Tunnel Historic District, which consists of a two hundred foot wide right of way along thirteen miles of original Denver, South Park and Pacific rail bed between the town sites of Quartz and Hancock.

Though the east portal of the tunnel collapsed many years ago and the west portal is covered by landslides, the district still provides a vivid peek into its prosperous early years. From Hancock westward the former rail bed is now a hiking trail. The west side can be accessed over a very rough road, also on the rail bed, to the restored railroad station house.

Though this 4-wheel drive trail is listed as “easy” by many resources, when Legends of America visited in 2006, we did not find it “easy” by any means and would never make the entire drive again in a jeep. The trail is primarily accessed today by ATV’s, which unfortunately, make the road an even rougher ride in an any kind of automobile.

That being said, it is a great trip. The Alpine Historical District is normally open from July to September, where a narrow dirt road winds upward to the tunnel for about ten miles.

Start your trip northeast of Pitkin, Colorado at the junction of the Cumberland Pass Road (FDR 765) and the Alpine Tunnel Road (FDR 839). Though the first seven miles or so are rough, we had no trouble making it up the grade in a four-wheel drive jeep. Along here you will see the old town sites of Quartz, Woodstock, and Sherrod, as well as numerous mining remnants, a restored railroad water tank, and remains of some of the old railroad tracks.

However, just beyond Sherrod, where the road comes to a “Y”, with one really rocky path leading to Hancock and the other to the Alpine Tunnel, the trail becomes very narrow, steep in places, and extremely rocky. This is the point that we would not traverse again in a jeep, and would recommend an ATV, mountain bike, or hiking only.

Though we are, by no means 4-wheel drive experts, this conclusion was also drawn from several locals and members of ATV groups in the area.

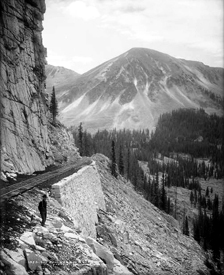

The trail, traveling across the old narrow gauge railroad bed is very narrow in places, especially when crossing the “Palisades,” a retaining wall, built of hand-cut stones without the use of mortar. The retaining wall is 432 feet in length and 33 feet in height with spectacular views.

The trail continues to the Alpine Station, where the remains of the old engine house can still be seen, as well as the restored station and telegraph office and the old railroad roundtable. Just short of the station, no ATV’s or vehicles are allowed, requiring visitors to walk a short distance to the station. The entrance to the west portal of the tunnel is on down about 1/8 of a mile.

The Palisades on the way down from the Alpine Tunnel, about 1900. Paywell Mountain stands in the background.